Last year, the World Bank argued that Africa is well-positioned to take advantage of new digital technologies – if governments can encourage innovation and investment to flow, including by increasing access to finance. This, the report argues, will unleash businesses to do what they do best: creating more and better jobs.

FSD Africa and other FSD programmes (collectively FSDs) across Africa aim to reduce poverty by developing financial markets and institutions across the continent. FSDs are shifting to a new strategy which emphasises jobs – both as a pathway out of poverty and as a driver of long-term economic transformation.

For the past year, The Good Economy – in collaboration with Tandem and FSD Africa’s results measurement team – has been designing and testing a framework to help FSDs more accurately measure the employment effects of financial sector deepening work [1]. For a start, the framework (access it here) has been tested on FSD Africa. This paper summarises the journey to developing this framework and what we have learned so far.

The jobs challenge and role of financial sector

Sub-Saharan Africa is believed to need 50,000 jobs a day just to accommodate young labour market entrants. Even where people are working, they are often not gainfully employed – with low wages and insufficient hours. For many countries on the continent the problem is not just one of unemployment, but underemployment.

The idea of a formal waged job as a pathway out of poverty is beyond the reach of many people. But while employment in many African countries is predominantly informal, the informal sector generates a substantial proportion of economic value add. In Mozambique, for example, informal jobs in the services or manufacturing sectors appear to be at least as productive as wage jobs.

If in the short-term low-quality employment will be the norm, one challenge is how to make these existing jobs incrementally better. But evidence on structural transformation also shows that higher-quality formal wage employment in modern sectors is the main engine of long-term growth and prosperity, so an additional challenge is how to start stimulating these new jobs now.

Financial systems can play a transformational role in boosting investment, growth, and job creation. A recent evidence review commissioned by CDC summarised the positive, causal relationship between improved quality and availability of financial services and economic growth. This happens in a myriad of ways – including overcoming access to finance constraints for small firms and facilitating more efficient capital allocation to high-growth firms [2].

We also know that market and institution building interventions deliver jobs impact – though their routes to this impact can be long-term and sometimes uncertain.

The framework

Measuring jobs is notoriously tricky to do well, particularly when aiming for a cost-effective approach that can be used in-house by FSD programmes (and FSD-like organisations). We developed a set of four design principles to guide the framework:

- Meaningful – Providing data about real impact and directional change over time, rather than simply describing jobs that can be linked in the broadest possible way to a project

- Transparent – Disclosing how jobs are calculated, as well as any limitations and caveats in the approach to allow the figures to be understood by internal and external stakeholders

- Conservative – Seeking to avoid overclaiming contribution to jobs by showing a range of job effects from a more conservative (base case) to a more optimistic (best case) scenario

- Proportionate – Using rigorous data, but recognising that generating jobs impact is just one of many aspirations that an FSD programme can achieve, or is expected to deliver.

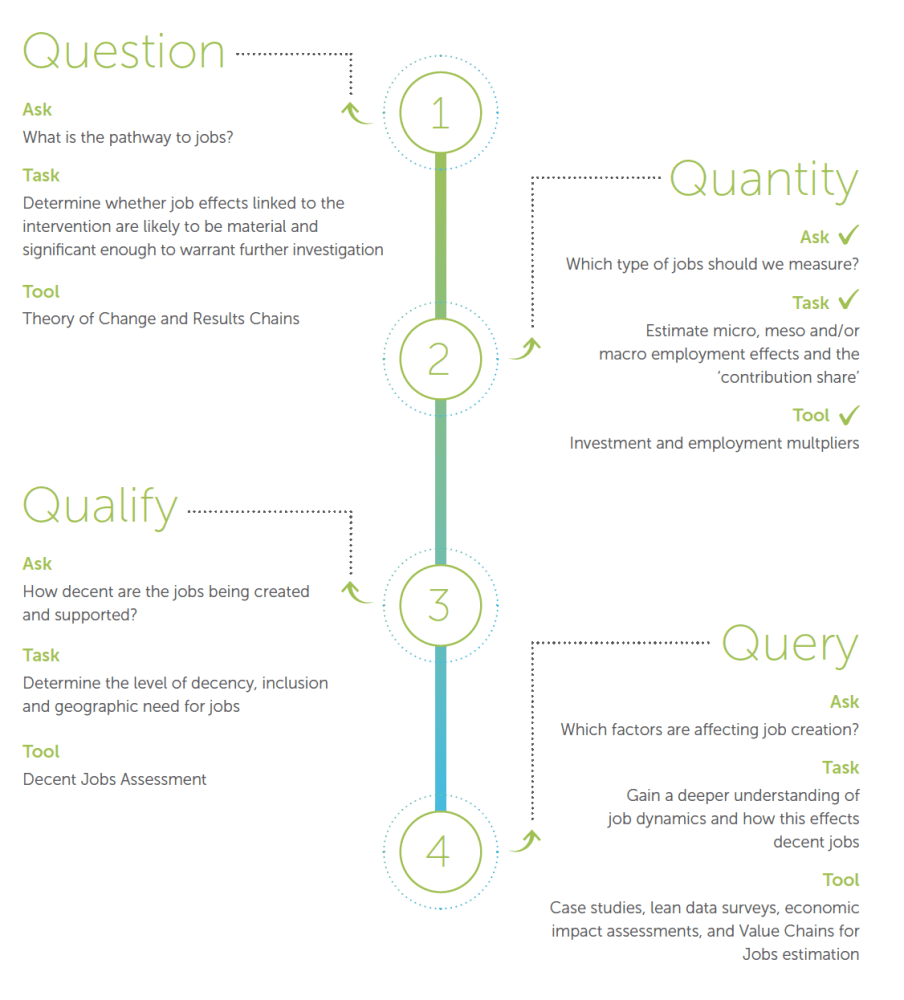

The first step in the framework involves a theory-based assessment of whether – based on the current evidence-base on how the financial sector supports job creation – a given project is likely to have a ‘material’ (any) or ‘significant’ (big enough) effect on employment to warrant further investigation.

The second step is to estimate job numbers using available primary data from project partners or financial service providers and then modelling any ‘indirect’ supply chain effects. This measures jobs created in firms benefitting from a financial sector innovation, and any supply chain jobs supported due to changes in output or demand from the beneficiaries of financing [3].

The third step is a ‘decent jobs assessment’ to examine the likely nature of jobs being supported, in terms of gender equality, inclusion of vulnerable groups, earnings, job security and career development prospects – using sector averages as proxies. This also factors in the relative need for job creation basedl-level SDG aligned indicators.

Finally, for projects with a large impact, or where there are questions about the strength of evidence, FSDs can choose to commission bespoke research to gain a deeper understanding of job dynamics in the real economy.

The learning

We have so far identified three key areas of learning:

First, the importance of accounting for jobs in full time equivalent (FTE) terms [4]. This is because job creation in areas with high underemployment is not always about creating new positions but adding to the stock of work for jobs that people already do. FTE allows portfolios to add ‘apples to apples’. For example, looking into the jobs impact of an investment by the housing financial catalyst Sofala, we drew on research by another FSD Africa partner, the CAHF, who found that “if there is increased construction activity, developers and contractors will first increase the amount of work undertaken by their existing workers, and only at a later stage – when there is sustained demand and work capacity is at or above 100 percent – would new employees be recruited into the sector”.

Second, it is important to move beyond narrow definitions of what constitutes a good job. It is commonplace to define quality jobs as those which exclude a single negative trait (such as those paying below a minimum wage); or including those that possess a positive feature (such as being in the formal sector). Rather, a sector-level profiling allows for a more nuanced qualification of the overall jobs numbers, which recognises the complex interplay between dimensions of job quantity, quality and inclusion [5]. For example, in many countries, construction sector jobs are characterized by short-term employment, high informality and low job security. However, thesbs can also be important to help youth enter the labour force and may create income-earning opportunities in areas where non-farm jobs are scarce. Ranking sectors based on the relative quality and inclusion of the type of jobs they create can act as a ‘decent work employment multiplier’. This is useful to measure the number of decent jobs directly and indirectly associated with an expansion in demand in any given sector. A sector may have a higher overall employment multiplier than another sector, but a lower decent work employment multiplier, and this can be factored into decision-making [6].

Finally, according to the International Labour Organization, a sectoral approach is particularly relevant as employment intensity varies significantly across the economy. In other words, not all sectors are ‘equal’ from a decent jobs perspective. This means it is important to not only examine the stock (total volume) of capital mobilised but also the flow into different sectors. Tracing financial sector innovations to changes in the real economy can be challenging. That said, it is an approach which fits with the new FSD strategy not just to address generic problems like the lack of SME finance, but to select economic sectors in which to focus before identifying the financial constraints affecting that sector (which may, in turn, be SME finance).

Already the framework has had important implications for FSD Africa – not only on how it measures its jobs impact, but also how it manages towards improving its jobs impact. More work is needed to refine the methodology, especially to collect better data to model indirect jand to develop a fair set of rules for estimating the ‘contribution share’. This would be best done with other like-minded institutions with a similar mandate of focusing on the financial sector in Africa. If this sounds like the organisation you work for, we’d love to hear from you.

By Matt Ripley (The Good Economy), Gareth Davies (Tandem), Kevin Munjal and Ryan Mwanzui (FSD Africa

- The framework was developed in consultation with the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. We would also like to thank colleagues from the “Jobs: Enhancing and Measuring Impact (JEMI)” for their feedback on the framework

- For FSD Africa, the two main mechanisms are access to capital: bringing more domestic savings into the formal financial system and attracting investment from overseas will allow long-term investment in the real economy; and Access to employment: boosting investment in the real economy allows firms to create jobs or make capital investments that raise productivity

- This translates part time or temporary employees into full time employees. For example, if two half time jobs are created of 120 days each per year, then that equals one FTE job

- This translates part time or temporary employees into full time employees. For example, if two half time jobs are created of 120 days each per year, then that equals one FTE job

- It also addresses data challenges, as the intermediated nature of financial systems means that extensive – or sometimes even any – primary data about the underlying jobs in beneficiary firms is not available.

- Employment Policy Department Working Paper No. 166: Sectoral dimensions of employment targeting

,